Having previously described the basic framework for an Episode of Care, let’s review a simple case study to bring it to life as well as highlight several other areas for further exploration.

As a review, an Episode of Care is designed to capture “the complete, self contained sequence of interactions between a patient and healthcare providers in pursuit of a defined clinical objective over a specified period of time.” Effectively, it is a single price for what may be a complex set of activities, potentially provided by a wide variety of actors, but to the end user and payer it appears as a single, bundled fee for the full set of services rendered. While Episodes of Care can be very complex depending on the condition, Crossover focuses on primary care and our associated services delivered as part of an integrated, comprehensive care model.

In our case study, we will use a simple case of pneumonia in an otherwise healthy software engineer (“Emily” is our 38 year old female security engineer, previous diagnosis of hypertension, but not currently on medication, and otherwise healthy) at a representative tech company.

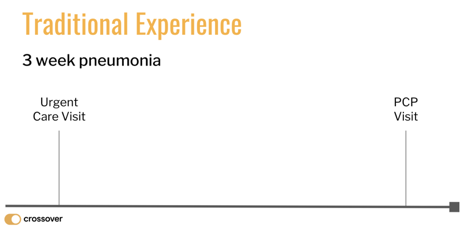

Traditional Care Model

In a traditional care model, Emily would have most likely dealt with the situation on her own for the first 4-5 days until the symptoms progressed to the point where she left work early one afternoon and visited an urgent care clinic in her home community. Given the fever, the productive cough, progressive symptoms, pervasive rales with mild wheezing, and a non-definitive but questionable X-ray, the provider chose to prescribe antibiotics, a short course of steroids, and an antitussive for symptomatic relief. A sputum culture was taken and sent off to the lab for confirmatory testing. The patient was told to take 2-3 days off work and call her primary care physician for a followup.

The patient went home with her after care summary, took her medication as prescribed, and generally rested for the next 3 days. Not feeling a whole lot better, Emily called a physician office referred by her friend but they couldn’t see her for two more weeks. Conditioned to expect this service level, she resigned herself to “powering through” and after another 3 days began to feel a bit better and returned to work a full seven days after the episode began. She never heard back from the urgent care, and she only remembered that followup appointment she had scheduled when her calendar invite popped up the night before. Given it was a light afternoon at work, she decided to keep the appointment since she didn’t have a primary care provider and thought it might be helpful to check in anyway. At the new doctor’s office Emily was required to repeat all her insurance information, sign a bunch of the same paperwork, and got less than 10 minutes with the physician who hurriedly ran through her story only to leave her with the distinct impression that there was no need to see him if she had already recovered. The physician vaguely referenced the opportunity for a more complete exam as part of establishing care with the practice, but left before any questions could be asked. Left feeling like she had just wasted her time as well as that of the practice, Emily left shaking her head what a terribly disjointed experience this entire situation had been.

The traditional care, as illustrated above, does not have any incentive to treat this patient holistically. The stops along the way are just transactions, and no single actor has an interest (economic or otherwise) to coordinate the full cycle of care for this condition. There is a beginning onset of illness and a fairly discrete endpoint (when the symptoms resolve) but there is really nothing happening in between these endpoints. Part of the problem is that the only way to engage care is by having an office visit, and these “meetings” are hard to coordinate, are usually inefficient, often feel like a waste of time, and no longer seem compatible with our digitally enabled asynchronous world. In addition, because the the payment model reinforces transactional compensation there is no incentive to organize the care or the providers in any other way. Therefore, discrete profit maximizing encounters that are optimized for individual actors and not for the entire episode (let alone the patient) are the norm. There is no communication between endpoints (there is no compensation for additional touchpoints), no connectivity (there isn’t a common platform of care that ties these actors together), and no coordination (no one is incented to support the patient).

This is healthcare AS IS, not Healthcare that just IS; Healthcare that remains fully discoordinated, not systematically connected; and healthcare fragmented, when it could be full stack.

Same example, but as an Episode of Care delivered by Crossver

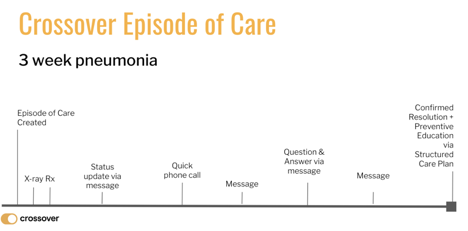

Let’s fast forward to a coordinated, connected system of health that leverages Episodes of Care to organize care, measure outcomes, manage risk, and increase value for all participants. In this case study, Emily’s employer sponsors an onsite clinic managed by Crossover where she created an account at the recent launch event to access her care team. As she is beginning to feel the onset of illness, her colleague suggests she ping the care team to see what they recommend. She logs in, selects the I’m Sick section, and fills out some basic information about her concerns. The app confirms the send, and provides her some basic reading information about Upper Respiratory conditions. In about 20 minutes she receives a text message that there was a response from her Crossover care team. She opens her mobile app and sees that there is a series of targeted questions related to symptoms she was describing. The note has a picture of the physician who responded as well as some links to other members of the care team. She answers the questions (all focused on her symptoms) and sends her responses back to her care team.

In about an hour, she receives another prompt from the care team that due to her constellation of symptoms, she should be seen in person for further evaluation. She chooses to set up an appointment in the morning instead of going to urgent care, which she knows is available 24/7. She is seen promptly the next morning at her scheduled time, surprised to be greeted by a host who knows her name, and is checked in with just her photo ID and a single click (given that she had already filled out her health information). She is roomed in less than five minutes and greeted by name by a nurse who completes her vital signs, reviews the Episode of Care information already shared, and confirms a few other things from her history.

Emily is next greeted by the physician whom she recognizes from the profile. A physical exam is completed with the same findings previously described, sputum sample sent, and an X Ray ordered (which she has performed on her way home after the visit – the care navigator had attached the imaging center details to a followup message). She is prescribed the same medications, given the same instructions but within the app for easy recall, and told the care team will check in with her in the next 48 hours. The physician reminds Emily that she can message anytime and if there are any emergency the practice has 24/7 call. The nurse reviews the instructions and hands Emily her medications. On the way out, Emily asks the host about her co-pay for the visit and is reminded that the credit card she has previously provided will be automatically charged. About 10 minutes after she’s left the Center, she sees that a message has arrived with the summary of her care, a clearly outlined Care Plan, and two followups to specific questions she had asked. The communication becomes the documentation and it is retrievable anytime she needs it. Emily is impressed, “Wow, that is healthcare as it should be!”

While the experienced described above sounds fantastic (and it is!), the magic of the Episode of Care for Emily is just beginning as you can see below.

Emily gets a status update message 2 days after her original visit. It includes a note from the nurse asking how she is feeling, with her radiology report attached to the message. Emily reports back that she is still not feeling great but steady. This message goes right to the physician’s queue who decides to check in on the lab culture to ensure the right antibiotics are prescribed. After reviewing the culture report, the physician decides to switch Emily’s medication and notify her by phone call. They review and discuss and the new prescription is sent to Emily’s preferred pharmacy and she picks it up while getting groceries. While picking up her medications, she has a question about potential interactions and sends a message to her care team. The question is promptly answered. Two days later she gets one last message asking how she is doing. Emily shares the good news she is feeling much better. The episode is closed out with some additional health information related to her pneumonia and a review of the structured care plan that was followed during the course of treatment. She reviews her experience, suggests touchpoints that were the most helpful, and anything about her care experience that could have been improved. Emily walks away with a strong impression about the level of coordination in person and online, the sense that the care team is working off a common plan, how all the interactions flowed like natural communications, and confident that she has an entire care team available to support her not just in sickness but more importantly in health. “Simple. Seamless. Surrounded. Just the way it should be” she again thinks to herself.

I believe this case study makes its own case – we effectively take the two uncoordinated in person “meetings” (estimated cost being ~$350 (UC + Imaging) for first visit and the second PCP followup PCP being $250 = Total $600) and we convert them into a global per Episode case rate that can be delivered for about 60-70% of the cost. The savings results from the integrated care team approach; software capabilities that ensure seamless connectivity, communication, and coordination throughout; and a business model that encourages the care team and the payer to look at the total bundle of services and pay for value as part of a defined episode. There are multiple financial nuances to this – including how Episodes get modified, how the payment model is scaled given specific variables, and how the financial translation between Episodes and the PEPM model can work. We can address all of these in future posts.

For now, the key is to compare the transactional nature of the two endpoint “visits” versus the continuum of interactions as represented in our “episode of care”. One stuck in the “tyranny of the visit” as the only means of interaction; and the other a fluid and multi-channel set of interactions throughout the full course of illness. One being bound by in-person only; and the other boundless with the in person, online, and anytime “micro-encounters” until the issue is resolved. One model stuck with analog technology; the other infused with asynchronous communication tools like messaging, emails, phone calls and even downloads of vetted health information.

Like so much of medicine – this all comes down to communication. As with our personal interactions everywhere else, the total of these interactions available in an Episode of Care enables a fuller picture of the person, provides numerous opportunities to track progress, pass along timely information, get advice of other members of the care team and, in general, demonstrate how the full care team can be engaged. Most importantly, Episodes of Care enable a new business model that by definition encourages the bundling of a set of services into a single, consumable package. And, I believe this bundling into Episodes of Care will unbundle an entire new value proposition for patients, providers, and payers.

2 comments on “The Episode of Care (Part 3): A Primary Care Case Study”